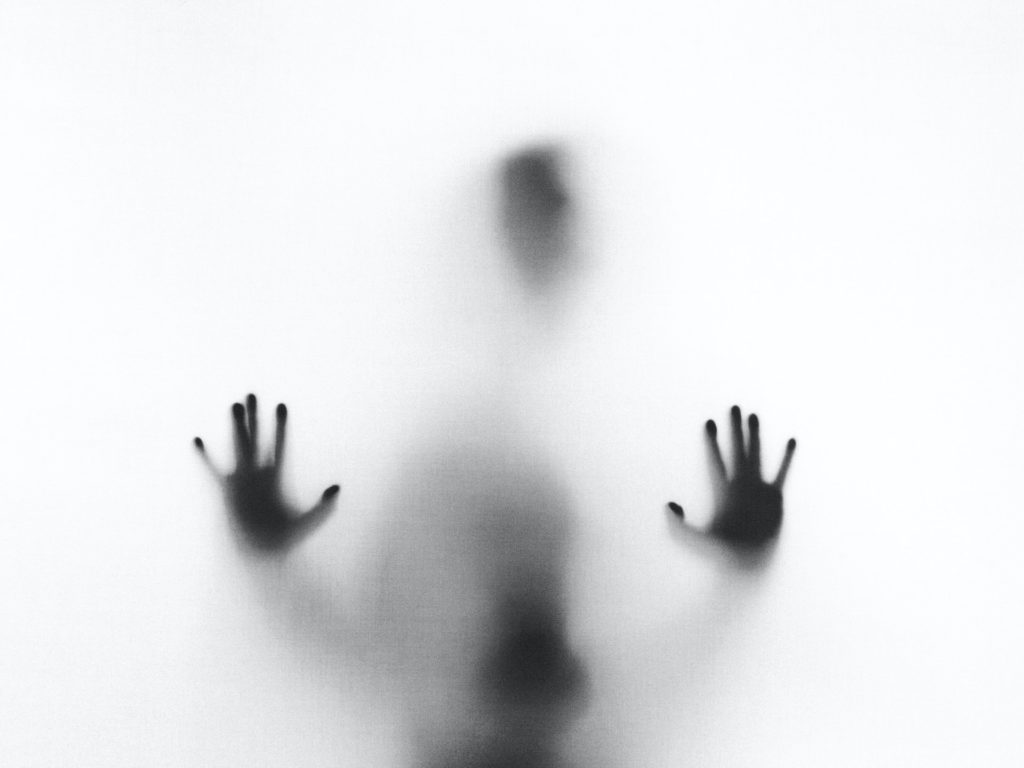

Mad, bad, or victim? (part 1)

During my bachelor’s degree, I had an enlightening course called “Mad or bad: a critical approach to counseling and forensic psychology”. It talked about how society, us humans, need to put people in boxes and label them. Especially people who do not fit in by acting and behaving in ways that betray the social norms. It’s easy to see this in action if you think about someone accused of a crime in a courtroom. Did they have all their mental capacity? Yes, then they are bad, or possibly evil. And if poor mental health prevented them from distinguishing right from wrong, then they are mad. Either way, we label them as people with a defect in their self-control. But this is not just in a courtroom, we do this all the time with anyone who defies our sense of morality. We are quick to call someone sick, crazy, dirty, dangerous, etc. And we don’t even realize how much race, gender, age, and social class play a role in how we label behaviors. Maybe some awareness is growing around the topic of race, thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement. But we are still so stuck and influenced by these unwritten societal rules and understandings. It is time to challenge them for a fairer and more resilient society.

The dark side of labeling

This university course also talked about how we perceive (and how the media portrays) highly controversial topics, such as sexual assault and abuse, sexual practices and preferences (homosexuality, sadism, masochism, transvestism, etc.), prostitution, questions around consent, but also self-harm, suicide, prevention, and treatments. Depending on our culture, gender, personal experiences, and values, we all have an opinion on these topics.

Homosexuality is a sad example of the ‘mad or bad’ debate. The American Psychiatric Association produces The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is the ‘bible’ of psychiatry to diagnose mental disorders. Homosexuality was listed as a sexual deviation in the first (1952) and second (1968) editions. Psychiatry and other ‘good intended’ practices have perceived homosexuality as a disorder (or an evil possession), something that must be treated and reversed. In the 70s, homosexuality was removed from the DSM, thanks to activism.

But to this day, some consensual sexual practices are still listed as mental disorders. They are also illegal in some countries. And so we should question whether we have any rights to label them in any way.

A useful label?

Of course, the mad and bad labels are important for prevention, treatment, and for containing those who are a danger to themselves and/or others. A diagnosis or judgment is often necessary to have access to certain services. And sometimes, it can also provide a sense of relief, a reason for unexplained and misunderstood behaviors, a community among those experiencing the same situation, etc. But there are also many issues with these labels. They are caricaturing and stigmatizing. They are also potentially worsening issues: when you keep telling someone they are troubled, and especially from a young age, they may eventually identify with this and unconsciously behave in a way to conform to this identity.

Everyone is at risk of becoming mad or bad

Anyone can at some point suffer from some poor mental health (I did), or act outside the law accidentally or intendedly. Studies show that most people will have in their life at least one type of mental disorder listed in the DSM. Depression is the most common disorder globally. Similarly, research also shows that many, if not a majority of people, will at some point in their life offend accidentally or intendedly, and risk becoming ‘bad’. As soon as you get caught offending or disturbing society with your mental health, that’s when you get the label. And once you get the label, it is extremely difficult to get rid of it, taking you down like a vicious circle. For instance, the younger people enter the justice system, the less likely they are to ever get out of it and turn their life around.

Who draws the line?

As we saw earlier with the example of homosexuality, the important question is how do we define who/what is mad, who/what is bad? Who has such moral authority to decide where to draw the lines? Things are not black or white, but the whole spectrum of grey in between. Behaviors take place on several continuums: severity, dangerousness, frequency. Drawing the line between the acceptable and the unacceptable is actually not scientific, nor universal, but rather vague, and potentially unfair.

What’s the point?

This doesn’t mean that mental health issues and offending behaviors do not exist, of course, they do. The aim here is to expand our perspective, get us out of the black-or-white box, and grow our empathy and resilience. When we look at ‘mad’ or ‘bad’ people and get interested in their personal life stories, we discover that there is favorable terrain for their struggles. Stress, trauma, abuse, neglect, biology all play a role, even more so when it comes from childhood. Traumatic events or circumstances that happen to children are called Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). This is what we will explore next…

How can you challenge the way you label people and their behaviors?

References:

Campion J, Bhui K and Bhugra D (2012) ‘European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders’, European Psychiatry, Vol. 27, pp. 68-80.

Mental Health Foundation (2020) Tackling social inequalities to reduce mental health problems: How everyone can flourish equally [Online]. Available at https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/MHF-tackling-inequalities-report_WEB.pdf

Vossler A, Havard C, Pike G, Barker M-J and Raabe B (2017) Mad or Bad? A Critical Approach to Counselling and Forensic Psychology, London, Sage.

WHO (2019) Mental health: Fact sheet [Online]. Available at http://www.euro.who.int.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/404851/MNH_FactSheet_ENG.pdf